Redemption beckons for Coleman

With Chris Coleman leading Wales to a major tournament for the first time in over half a century, Leon Barton looks back at what led to Coleman’s moment of history.

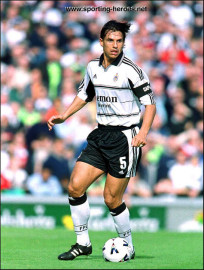

May 14th 2002; It’s injury time at the Millennium Stadium and the score is still Wales 1 Germany 0. Debutant and goalscorer Robert Earnshaw of Cardiff City is leaving the field, and the majority of the 37,000 people inside the ground are on their feet, not just to salute the local hero, but to greet the long-awaited return to action of the waiting substitute. Son-of-Swansea Chris Coleman is about enter the field and the Cardiff crowd is loving it. 17 months on from the car crash that could have killed him, Wales is welcoming back a defender of class and experience to augment a team that finally looks capable of competing for qualification again at long last. It’s a spine tingling moment, not just poignant, but also one rich with promise. After all, we’re about to beat the mighty Germans, and now our best defender is back! The campaign to get to the 2004 European championships begins in Finland in a little over three months time. How much are flights to Helsinki?

It remains one of my all time favourite moments watching Wales , even though the promise was never fulfilled. It was to be Coleman’s final appearance as a professional footballer. He was just 31 years old at the time.

It didn’t take long for Coleman to embark on the next phase of his footballing life. A hugely respected figure at his club, Fulham, having captained them from the depths of the third tier to the verge of the big time (Coleman crashed his car just months before Fulham were promoted), he soon joined the Jean Tigana’s coaching staff, and when Tigana was dimissed the following April he was appointed Fulham FC manager. At just 32 years old, he remains the Premier league’s youngest ever boss.

How did a player of such class end up in the 3rd tier? Chairman Mohamed Al- Fayed’s millions skewed the picture somewhat. His appointment of Kevin Keegan was a sign of the ambition he had for the club he dreamed of making the ‘Manchester United of the south’. Perhaps learning the lessons of his hugely entertaining but ultimately disappointing time at the helm of Newcastle, Keegan decided to build from the back, with Coleman’s arrival for 2 million pounds a key piece in the jigsaw. Keegan called him ‘the best player outside the top flight’. He was about to get back to the level he belonged at when the crash happened. As has often been the case throughout his football career, it was another case of nearly but not quite.

How did a player of such class end up in the 3rd tier? Chairman Mohamed Al- Fayed’s millions skewed the picture somewhat. His appointment of Kevin Keegan was a sign of the ambition he had for the club he dreamed of making the ‘Manchester United of the south’. Perhaps learning the lessons of his hugely entertaining but ultimately disappointing time at the helm of Newcastle, Keegan decided to build from the back, with Coleman’s arrival for 2 million pounds a key piece in the jigsaw. Keegan called him ‘the best player outside the top flight’. He was about to get back to the level he belonged at when the crash happened. As has often been the case throughout his football career, it was another case of nearly but not quite.

He arrived at Fulham from Blackburn Rovers, who signed him when they were Premier league champions. Having performed consistently well for Crystal Palace, Rovers saw his signing as a way to strengthen their power in league and help make an impact in Europe. Nothing of the sort happened as Coleman, stuggling with a persistant archilles problem only managed around thirty appearances in his spell there. A shame, as that was his shot at the big time as a player; to challenge for trophies, to play regular European club football. Nearly but not quite.

At international level Coleman had a great start, scoring on his debut in a 1-1 draw in Austria. He was always good for a goal and it was great to see how much it meant to him to score for Wales. His celebrations upon scoring the equalizer in a a thrilling 3-2 win over Belarus in 1998 showed clearly what it meant to him and his record of 4 international goals in 32 games compares favourably with current forwards like Simon Church (2 in 31) and Hal Robson-Kanu (2 in 28) But, it was at the other end of the pitch where his class was needed most.

It’s perhaps not saying much, but in the mid to late 90’s Chris Coleman was clearly Wales’ best defender; strong in the air, comfortable with the ball at his feet and a good reader of the game with a huge heart. A shame then, that there was always feeling that he had a mistake in him. Against Italy at Anfield in 1998, he gifted the ball to Diego Fuser, a promising start with Giggs and Blake causing the Italian defence all sorts of problems squandered in a split second of lost concentration.

Upon being appointed Wales manager at the turn of the millennium, Mark Hughes worked hard to improve the team’s defensive resolve. It was clear, after years of humiliating thrashings, not just vs the big boys like Holland and Italy, but also against the likes of Georgia and Modolva, that it was an area of the pitch which required urgent attention. During the ultimately disappointing campaign to qualify for the 2002 World cup, signs of a promising new defensive resolve were evident. A 0-0 draw in Poland the first competitive clean sheet for a while – a useful and hard-fought for point vs a good team in a hostile atmosphere. By that point, Hughes had decided Coleman was to be his regular left back, a postion he could play, having started off there as a youngster at Swansea City, and we looked a lot more solid with that change having taken place. Something needed to be done as full back was an area of the pitch where we were really struggling. Mark Delaney’s move to Aston Villa in 1999 at least ensured that we had a classy player on that side of the pitch. Left back continued to be a problem for years, so much so that Hughes thought the best way to solve it following Coleman’s crash was to ask Gary Speed – probably our best central midfielder – to play there instead. Speed did a fine job, but it was always clear it was far from his best position.

Our full back issues at the end of the 90’s and beginning of this century are a far cry from where we find ourselves now, with Chris Gunter, Neil Taylor, Jazz Richards and Ben Davies all having proved themselves classy performers on the international stage.

The Poland away performance, which promised so much from a defensive point of view, was to be Coleman’s last Wales start. Nearly, but not quite.

I don’t want to go into Coleman’s managerial career in too much detail here as fellow Podcast Pêl-droed contributor Hwyel has already done that an an excellent piece which attempted to redress the balance in the face of ‘Coleman’s managerial career has been a total failure’ write-offs. He did well at Fulham, taking over a good team from Jean Tigana, but adding to it, bringing in players like Simon Davies and Jimmy Bullard, who performed well for the club even after his departure. Certainly, off-field distractions didn’t help towards the end of his tenure. I don’t want to talk specifics here because tabloid shit doesn’t interest me, but it can’t help on-field matters much when a manager is being asked about his personal life as much as football.

At Real Sociedad, he left with the club near the top of the Segunda Division but again, off-field distractions tainted his time there. Given a massive opportunity to revive the fortunes of one of Spanish football’s big teams, I would like to think Coleman himself now realises he didn’t help himself there with his unprofessional behaviour.

At Coventry, it’s often forgotten that he started well, leading the (then) championship club to an FA cup quarter final. Coventry were second tier when he arrived and they were still second tier when he was sacked. Their descent into lower league mediocrity came after Coleman left. Financial problems have blighted Coventry for years and to be honest I wouldn’t have fancied Morinho or Wenger to have done any better there. It’s not something I can confirm, but I have heard that Coventry had a bid of under half a million pounds for a young striker by the name of Andy Carroll accepted by Newcasle United during Coleman’s time in charge. Coventry’s board changed their mind and vetoed the deal, not believing it represented good value. A couple of years later Carroll did move. To Liverpool. For 35 million quid.

Where do you go after getting sacked by Coventry City? To the Greek second division of course. Although Larissa were doing well when he left, Coleman had not been paid for several months, and as soon as the call came to replace his late friend Gary Speed and become manager of his country, I doubt he could have jumped on the plane any sooner.

It’s fair to say he wasn’t a popular choice amongst Welsh fans at the time, many critisizing the move in a vocal manner. And admittedly, I was one of them.

For me, it wasn’t so much his managerial track record I found problematic (I’m a realist, Wales are never going to get a European Cup winning coach on board) it was more his media demeanour. As a Wales fan of nearly thirty years, frankly I’d had enough of failure and excuses, and I couldn’t see someone with Coleman’s manner changing that. I wanted to hear some postive intent – ‘we’ve got great players, we should be challenging for qualification’ etc – we heard nothing of the sort from Coleman at first.

Given the players available to us, there’s no way we should have been losing 6-1 to the likes of Serbia, and Coleman at that point looked as lost as the team, unable to put forward any logical reason for our sheer awfulness in that game.

Decent results, and performances, home and away to Scotland bought him time, but by the point of the ‘passport incident’ with Coleman unable to travel with the team to Macedonia, the knives were out once more. With a Bale-less Wales losing the game in Skopje they were well and truly being sharpened.

The two matches at the end of the 2014 world cup campaign pretty much kept Coleman in a job, something he himself has appeared to acknowledge. With several players missing- notably Gareth Bale and captain Ashley Williams- achieving 4 points in the two games vs Macedonia (at home) and Belgium (away) with everyone’s backs to the wall, was huge in the circumstances.

And so to the Euro 2016 campaign. The awful, stressful, scrappy 2-1 win in Andorra did little to alleviate the feeling that Coleman was out of his depth, and little was likely to improve during his tenure. The knives came out once more. Personally, I was just relieved to get out of there with the three points, but the media criticism was vicious. Coleman must have known getting something out of the Bosnia home game in October 2014 was vital to get the press off his back. The 0-0 draw, for me, was a massive turning point. With our midfield decimated by injury – Ramsey, Allen, Vaughan and Huws all out – the likes of Joe Ledley and relative newcomer James Chester refused to buckle under intense Bosnian pressure, gaining a hugely gutsy point in the circumstances. This was the game where the bullish Coleman emerged. ‘We got bullied when we played Bosnia before… we didn’t get bullied tonight’

Sometimes, the circumstances dictate that someone never before considered part of the ‘big league’, finds himself in the right place at the right time, and is at least given the opportunity to make a massive mark.

Chris Coleman has Gareth Bale at his disposal, someone in the process of turning himself into the greatest Welsh footballer of all time. Aaron Ramsey will almost certainly go down as Wales’ greatest ever central midfielder and Ashley Williams is already one of the great Welsh defenders and captains. As well as Coleman has done in getting the best out of these players on the international stage, his track record at club level suggests he is unlikely to manage players with this much quality on a day-to-day basis. Coleman as Real Madrid or Arsenal manager is difficult to picture. As Rich said in Podcast Pêl-droed #16, Coleman now knows this is his Oscar-winning role… like Cuba Gooding Jr. in Jerry Maguire’

But even greatness needs to be managed. We’ve had great players before, we still never qualified. But during the course of this campaign, we’ve seen a growing and genuine belief that we will be at the European Championships in 2016. Chris Coleman has lead this charge superbly. It’s difficult to think of a single foot he has put wrong since the end of the last campaign and he deserves massive credit for leading Welsh football into unchartered waters. For us fans these are heady times. For the manager redemption beckons.

One more measly point, and he’s the nearly man no more.

Featured image courtesy of Wales Online